Empty store shelves, out-of-stock products, and apologetic salespeople citing shipment delays are some of the main reasons for customer dissatisfaction. Sure enough, the blame can be pinned on a lack of proper supply chain logistics.

But, look a bit more deeply, and we might see this thing called port congestion that figures more often among reasons for stock-outs. The tremendous increase in global business volumes also necessitates logistics operators to be constantly on their toes to handle the increased volumes effectively.

Port congestion is overcrowding at a seaport that gives rise to all kinds of problems for stakeholders such as the shipper, carrier, consignee, as well as the port’s administration. The cause for overcrowding could be one or several.

Sometimes a single reason can have a cascading effect causing untold distress to the stakeholders. Congestion is often a result of the changing requirements of stakeholders.

Port Congestion and Supply Chains

Disruption in committed delivery timings can upset supply chains and exhaust inventories. It can also lead to a build-up of stock when the flow of traffic is regularised and pre-ordered stocks start coming in. In this case, stocks on board a vessel that was delayed, as well as regular supplies, reach their destination within a short gap or even sail in together!

Global supply chains are affected because port congestions and inventory plans get upset. Port congestions result in containers having to wait for more time to berth. The longer time required for berthed and loaded vessels to leave the port is the reason behind this conundrum.

In recent times, the coronavirus pandemic caused a major slowdown and, in some cases, a complete shutdown of operations at ports and business centres. Later on, when such operations resumed, and things started limping back to normal, the extra volumes and traffic of cargo created congestion at ports. Ports that were already burdened could not handle the extra volumes.

In this case, cargo ships were unable to berth and had to wait long periods to get berthing slots. They had to wait outside at anchorage for their turn to berth. Infrastructure and machinery limitations further slowed down activities. With very few automated port terminals in the world, labour shortages meant very long delays.

The delay of one vessel meant delays for those waiting in line. More vessels in the queue to berth means wasted fuel consumption as well as the discharge of more effluents into the sea. Human wastes from ships and bilge water damage the marine ecosystem.

Port congestion may be caused by natural calamities, or it may be due to man-made conflicts.

Reasons for Port Congestion

Force Majeure

Force majeure or the Act of God are unavoidable factors that cause port congestion. This French term, meaning “an inevitable, greater force”, covers natural phenomena such as earthquakes, pandemics, storms, rough seas, etc.

Interestingly, human conflicts such as armed violence or civil unrest, as well as labour strikes, also come under the force majeure clause. Generally, force majeure factors are not considered when it comes to compensation for delays or damages.

Let us look at some of the main factors here.

Pandemics

Pandemics and other health-related disasters can affect staff and labour attendance that is required to run the operations of a port terminal. The coronavirus pandemic, which began in December 2019, is a prime example of how a pandemic can affect port operations.

When the workforce is down, shore-side operations get affected badly. Even after recovering from the pandemic, it might take quite a long time to undo the chaos created by the backup of ships.

Bad Weather

Storms and rough seas can prevent ships from berthing at certain ports or sailing out of channels safely. Ships then have to wait for the inclement weather to abate, causing a long queue of ships to come in as well as sail out of the port terminal.

Lack of Port Infrastructure

Not all ports are developed and equipped with state-of-art cargo and container handling equipment. Nor will some have the necessary storage space to hold containers and other cargo. Booking cargo and berthing slots of ships without considering these factors can cause serious port congestion.

Labour-related Issues

Labour disputes and strikes can cause operations to slow down drastically or even grind to a complete halt. Last year, a strike by dock workers affected some German ports. Separately, labour unions of the ports of Liverpool and Felixstowe, UK, went on strike protesting over contract negotiations. Similarly, the Finnish port workers went on strike in February this year, affecting operations of all the major ports in Finland for about two weeks.

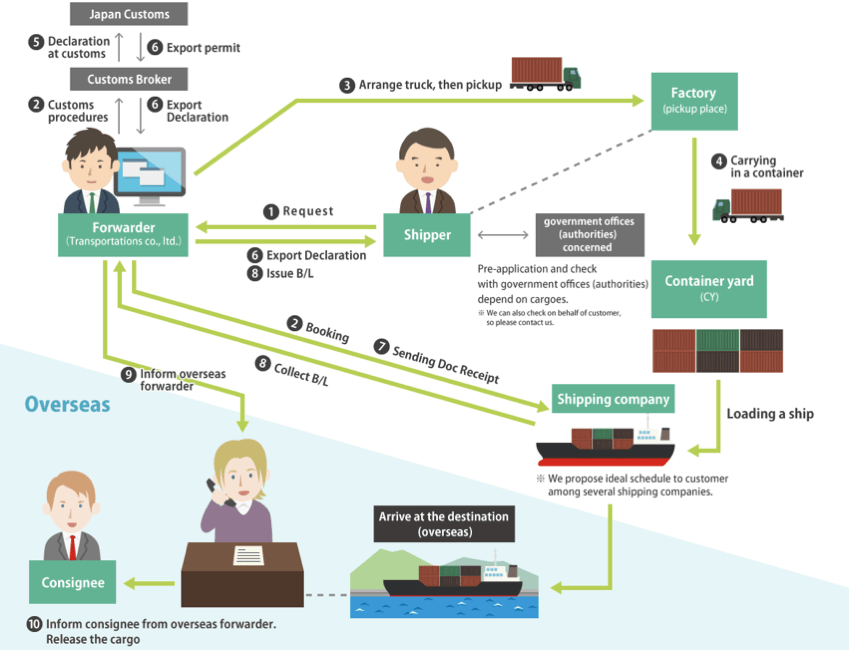

Lengthy or Complicated Customs Clearance Procedures

Some countries have complicated customs procedures for imports as well as exports. Some of these formalities can be completed only upon the arrival of a ship. Lack of digitalisation and effective communication can add to the woes here, causing a backlog of clearance or export.

How can Supply Chains Overcome Port Congestions?

Dividing bulk orders and having them shipped on multiple vessels to different but nearby ports is one method to overcome port congestion. This is so that even if one consignment is stuck at the main port due to congestion, the rest can be received from other ports. This method is more expensive and will require longer overland transit to bring such goods from the nearby ports.

Overall, for the business, it might work out better than having all the cargo stuck at one congested port. However, this is possible only if there are one or more ports nearby or conveniently accessible.

Having an efficient supply chain that splits the order quantities to stagger the arrival dates slightly is another option to avoid complete stock-outs.

Blank Sailing

Carriers overcome port congestions through blank sailings. When a ship skips a port that is congested and instead sails directly to its next port of call, it is called blank sailing. Such sailings affect the carrier, shipper, consignee, and the port authority in question, where they lose valuable revenue.

To overcome the problem of port congestion, supply chains have become more flexible these days and often opt for overland transport or air freight to bring in their cargo and overcome emergencies.

Port Congestion at Leading Ports

For comparison, one of the busiest ports in the US, the Port of Houston, has a current cargo waiting time of 4-5 days. The busy ports in India fare better. The Mundra Port and the JNPT (Nhava Sheva) have an average waiting time of 1-2 days for discharging incoming cargo.

Port Congestion Surcharge (PCS)

Some carriers charge a port congestion surcharge to cover the costs caused by delays. Recently CMA CGM introduced a port congestion surcharge of $100 per unit for consignments sailing from the Port of Mersin, Turkey, to the Indian subcontinent to cover their costs due to traffic congestion.

Source: Marine Insight

What is an ATA Carnet?

What is an ATA Carnet?