Who would have guessed that a collection of three-letter acronyms would have had such an impact on the development of international (and domestic) commercial transactions? We can thank a group of industrialists, financiers and traders whose determination to bring economic prosperity to a post-World War I era eventually led to the founding of the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC). With no global system of rules to govern trade, it was these businessmen who saw the opportunity to create an industry standard that would become known as the Incoterms® rules.

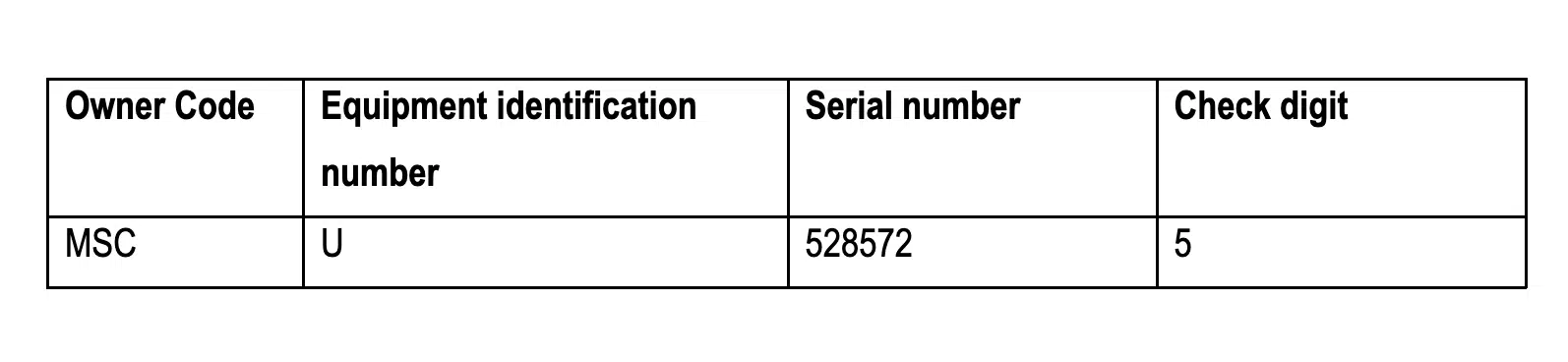

Below are short descriptions of the 11 rules from the Incoterms® 2020 edition.

EXW (EX Works) means that the seller has only to place the goods at the disposal of the buyer, at the seller’s premises or at another named place. Seller does not have any other obligation. Any other task of export & import clearance, carriage and insurance is to be arranged by the buyer.

FCA (Free Carrier) means that the seller delivers the goods to the carrier or another person nominated by the buyer at the named place. The parties must specify as clearly as possible the point in the named place of delivery. The risk passes to the buyer at that point.

FAS (Free Alongside Ship) means that the seller delivers when the goods are placed alongside the vessel at the named port of shipment. The seller is obliged to clear the goods for export. From the moment, when the goods are alongside the ship, all costs and risks pass to the buyer. This term can be used for ocean transport only.

FOB (Free On Board) means that the seller delivers when the goods pass the ship’s rail at the named port of shipment. The buyer has to bear all costs and risks to the goods from that moment. The seller must, also, clear the goods for export. This term can be used for ocean transport only.

CFR (Cost and Freight) means that the seller delivers when the goods pass the ship’s rail in the port of shipment. Seller pays the cost & freight necessary to bring the goods to the named port of destination. Also, seller must clear the goods for export. But, the buyer has to bear the risk of loss or damage, as well as any additional costs due to events occurring after the time of delivery. This term can only be used for ocean transport.

CIF (Cost, Insurance and Freight) means that the seller delivers when the goods pass the ship’s rail in the port of shipment. Seller pays the cost & freight necessary to bring the goods to the named port of destination. Seller must clear the goods for export. Risk of loss & damage same as CFR.

The seller also contracts for insurance cover against the buyer’s risk of loss of or damage to the goods during the carriage. The seller is obliged to obtain the minimum marine insurance protection. If the buyer wants to have more insurance protection, it will need either to agree as much expressly with the seller or to make its own extra insurance arrangements.

CPT (Carriage Paid To) means that the seller delivers the goods to the carrier or another person nominated by the seller at an agreed place. The seller must contract for and pay the costs of carriage necessary to bring the goods to the named place of destination. After that moment, the buyer bears all costs. The seller must, also, clear the goods for export. This term may be used irrespective of the mode of transport (including multimodal).

CIP (Carriage And Insurance Paid To) is the same as CPT with the exception that the seller must obtain the minimum marine insurance protection. If the byer wishes to have more insurance protection, it will need either to agree as much expressly with the seller or to make its own extra insurance arrangements.

DAT (Delivered At Terminal) means that the seller delivers when the goods, once unloaded from the arriving means of transport, are placed at the disposal of the buyer at a named port or place of destination. “Terminal” includes a place, whether covered or not, such as quay, warehouse, container yard or road, rail or air cargo terminal. Seller pays for carriage to the terminal, except for costs related to import clearance. In addition, seller bears all risks involved in bringing the goods to and unloading them at the terminal at the named port or place of destination.

DAP (Delivered At Place) means that the seller delivers when the goods are placed at the disposal of the buyer on the arriving means of transport ready for unloading at the named place of destination. The seller pays for carriage to the named place, except for costs related to import clearance and bears all risks prior to the point that the goods are ready for unloading by the buyer.

DDP (Delivered Duty Paid) means that the seller delivers the goods when the goods are placed at the disposal of the buyer. The goods must be cleared for import on the arriving means of transport ready for unloading at the named place of destination. The seller bears all the costs and risks involved in bringing the goods to the place of destination. In addition, the seller is obliged to clear the goods for export and import. The seller has also to pay any duty for both export and import and to carry out all customs formalities, including the payment of taxes and custom fees.

WE JOURNEY THROUGH 80 YEARS OF MILESTONES FOR THE COMMERCIAL TRADE TERMS THAT HAVE TRANSFORMED THE GLOBAL TRADE INDUSTRY.

1923: ICC’s first sounding of commercial trade terms

After ICC’s creation in 1919, one of its first initiatives was to facilitate international trade. In the early 1920’s the world business organization set out to understand the commercial trade terms used by merchants. This was done through a study that was limited to six commonly used terms in just 13 countries. The findings were published in 1923, highlighting disparities in interpretation.

1928: Clarity improved

To examine the discrepancies identified in the initial survey, a second study was carried out. This time, the scope was expanded to the interpretation of trade terms used in more than 30 countries.

1936: Global guidelines for traders

Based on the findings of the studies, the first version of the Incoterms® rules was published. The terms included FAS, FOB, C&F, CIF, Ex Ship and Ex Quay.

1953: Rise of transportation by rail

Due to World War II, supplementary revisions of the Incoterms® rules were suspended and did not resume again until the 1950’s. The first revision of the Incoterms® rules was then issued in 1953. It debuted three new trade terms for non-maritime transport. The new rules comprised DCP (Delivered Costs Paid), FOR (Free on Rail) and FOT (Free on Truck).

1967: Misinterpretations corrected

ICC launched the third revision of the Incoterms® rules, which dealt with misinterpretations of the previous version. Two trade terms were added to address delivery at frontier (DAF) and delivery at destination (DDP).

1974: Advances in air travel

The increased use of air transportation gave cause for another version of the popular trade terms. This edition included the new term FOB Airport (Free on Board Airport). This rule aimed to allay confusion around the term FOB (Free on Board) by signifying the exact “vessel” used.

1980: Proliferation of container traffic

With the expansion of carriage of goods in containers and new documentation processes, came the need for another revision. This edition introduced the trade term FRC (Free Carrier…Named at Point), which provided for goods not actually received by the ship’s side but at a reception point on shore, such as a container yard.

1990: A complete revision

The fifth revision simplified the Free Carrier term by deleting rules for specific modes of transport (i.e., FOR; Free on Rail, FOT; Free on Truck, and FOB Airport; Free on Board Airport). It was considered sufficient to use the general term FCA (Free Carrier…at Named Point) instead. Other provisions accounted for increased use of electronic messages.

2000: Amended customs clearance obligations

The “License, Authorizations and Formalities” section of FAS and DEQ Incoterms® rules were modified to comply with the way most customs authorities address the issues of exporter and importer of record.

2010: Reflections on the contemporary trade landscape

Incoterms® 2010 is the most current edition of the rules to date. This version consolidated the D-family of rules, removing DAF (Delivered at Frontier), DES (Delivered Ex Ship), DEQ (Delivered Ex Quay) and DDU (Delivered Duty Unpaid) and adding DAT (Delivered at Terminal) and DAP (Delivered at Place). Other modifications included an increased obligation for buyer and seller to cooperate on information sharing and changes to accommodate “string sales.”

2020: Looking ahead

To keep pace with the ever evolving global trade landscape, the latest update to the trade terms is currently in progress and is set to be unveiled in 2020. The Incoterms® 2020 Drafting Group includes lawyers, traders and company representatives from around the world. The overall process will take two years as practical input on what works and what could possibly be improved will be collected from a range of Incoterms® rules users worldwide and studied.

Source: Container News

Besides, the market is replete with products from multiple carriers, which have little to differentiate between them. Shippers and Exporters have been focussing on freight spending and displaying an increasing propensity to prioritise lower rates over faster transit times, which further perpetuates the trend of commoditisation (due to the reduced commercial viability, Carriers have little incentive to offer shorter times in the absence of demand).

Besides, the market is replete with products from multiple carriers, which have little to differentiate between them. Shippers and Exporters have been focussing on freight spending and displaying an increasing propensity to prioritise lower rates over faster transit times, which further perpetuates the trend of commoditisation (due to the reduced commercial viability, Carriers have little incentive to offer shorter times in the absence of demand).